MAIN PUBLICATION :

| Home � ENVIRONMENT � Environmental impacts � Impacts on marine mammals and sea birds |

|

Impacts on Marine Mammals and Sea Birds

IMPACTS ON MARINE MAMMALS

Offshore wind farms can negatively affect marine mammals, both during construction and operation stages. The physical presence of turbines, the noise during construction, the underwater noise as well as boat and helicopter traffic can disturb mammals causing them to avoid wind farms.

Monitoring marine mammals living and moving is very difficult. Fortunately, the traditional visual surveys from ships and aircraft are being supplemented or replaced by new, more accurate technologies such as acoustic monitoring by stationary data loggers, remotely controlled video monitoring and tagging of individuals with satellite transmitters.

Mammals are very dependent of their hearing systems that are used for several purposes: communication between other individuals of the same species, orientation, finding prey and echolocation. The behavioural response by marine mammals to noise includes modification of normal behaviour, displacement from the noisy area, masking of other noises, and the impossibility of acoustically interpreting the environment. The consequences from this disturbance could cause problems of viability of individuals, increased vulnerability to disease, increased potential for impacts due to cumulative effects from other impacts such as chemical pollution combined with stress induced by noise (Greenpeace, 2005).

The noise measured by the German Federal Ministry of Environment doesn't seem to damage the hearing organs of marine animals, but it is not well known how it will affect their behaviour in the area surroundings the turbines. Although the sound level is moderate, it is permanent (until decommissioning), thus more research about its influence on marine animals behaviour is needed (Koeller et al, 2006).

Horns Rev and Nysted wind farms in Denmark have carried out a comprehensive environmental monitoring programme between 1999 and 2006, covering baseline analysis, construction and operation phases. The highlight of the study shows different reactions between seals and porpoises. Seals were only affected during the construction phase, due to the high sound levels in pile diving operations. In the operation phase, it seems wind farms did not have any effect on seals. However, harbour porpoises' behaviour was dissimilar at the two offshore wind farms. In Horns Rev, the population decreased slightly during construction, but recovered to the baseline situation during operation. In Nysted, porpoise densities decreased significantly during construction and only after two years of operation did the population recover. The reason for this slow recovery is unknown (DEA, 2006).

Nysted wind farm is located 4 km away from the Rosland seal sanctuary. The presence of the wind farm had no measurable effects on the behaviour of seals on land (DEA, 2006).

The foundations of wind farms create new habitats, which are colonised by algae and benthic community. This further availability of food may attract new species of fish and subsequently mammals. This change could be neutral or even positive to mammals.

It is very difficult to assess the long-term impacts on reproduction and population status with the current state of knowledge. The possible behaviour modification of marine mammals due to the presence of wind turbines at sea is presumably a species-specific subject. Other factors which also require further research relate to oceanographic parameters (hydrography, bathymetry, salinity and so on) and the hearing systems of mammals (Koeller et al, 2006).

IMPACTS ON SEA BIRDS

The influence of offshore wind farms on birds can be summarised as follows:

- Collision risk;

- Short-term habitat loss during construction phase;

- Long-term habitat loss due to disturbance from wind turbines installed and from ship traffic during maintenance;

- Barriers to movement in migration routes; and

- Disconnection of ecological units.

(Exo et al, 2003)

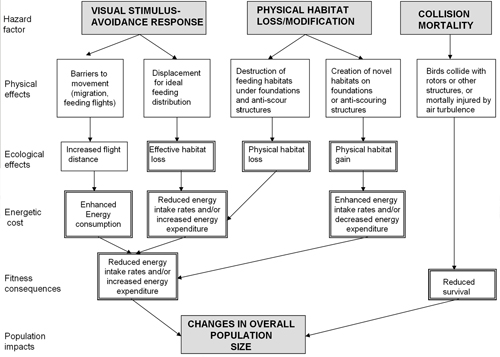

The methodology proposed by Fox to support EIAs of the effects on birds of offshore wind farms reveals the great complexity of the analysis. The relationships between offshore wind farms and bird impacts must be analysed by gathering information about avoidance responses, energetic consequences of habitat modification and avoidance flight, and demographic sensitivity of key species (Fox et al, 2006).

Figure 2.2: Flow Chart of Hazards Factors to Birds by Offshore Developments.

Note: Boxes with a solid frame indicate measurable effects, boxes with a double frame indicate processes that need to be modelled.

Source: Fox et al. (2006), courtesy of the British Ornitologists' Union (BOU)

Collisions have the most direct effect on bird populations. Collision rates for wintering waterfowls, gulls and passerines on coastal areas in northwest Europe range from 0.01 to 1.2 birds/turbine. No significant population decline has been detected. Direct observations from Blyth Harbour, UK, have demonstrated that collisions with rotor blades are rare events in this wind farm located within a Site of Special Scientific Interest and Special Protection Area, under the Birds Directive (Lawrene et al in de Lucas et al, 2006).

In poor visibility conditions, large numbers of terrestrial birds could collide with offshore wind farms, attracted by their illumination. However, this occurs only on a few nights. Passerines are the group mainly involved in these collisions. One of the most useful mitigation measures to avoid this type of impact is to replace the continuous light with an intermittent one (Huppop et al, 2006).

Information about bird mortality at offshore wind farms is very scarce for two reasons: the difficulty of detecting collisions and the difficulty in recovering dead birds at sea. Further investigations on this topic are needed to get reliable knowledge (Huppop et al, 2006).

There is a lack of good data on migration routes and flight behaviour of many of the relevant marine bird species (Drewitt and Langston, 2006; Exo et al, 2003). But this data is essential for assessing the potential impacts of collisions and barriers to movements (Drewitt and Langston, 2006; Huppop et al 2006). The large scale of proposed offshore wind farms together with the expected cumulative effects increase the need to fill in these gaps.

The degree of disturbance differs between different species. The disturbance may be determined by several factors such as availability of appropriate habitats, especially roosting and feeding areas, time of year, flock size and the layout of the wind farms (Exo et al, 2003).

Disturbances during construction are produced by ships and/or helicopter activities and noise generated by ramming piles. After that, in the operation stage, disturbances by boat traffic have an impact on birds (Exo et al, 2003).

The impacts of marine wind farms are higher on sea birds (resident, coastal and migrant) than on onshore birds. The reasons for this higher impact at offshore developments is related to the larger height of marine wind turbines, the larger size of wind farms and the higher abundance of large bird species, which are more sensitive to disturbance (Exo et al, 2003).

The most important findings after seven years monitoring Horns Rev and Nysted wind farms indicate negligible effects on overall bird populations. The majority of bird species showed avoidance of the wind farms. Although there was considerable movement of birds around wind farms, however, between 71-86 per cent of flocks avoided flying between the turbine rows of the wind farm. Changes in flying directions, for most of the species, were verified at 0.5 km from wind farms at night and at 1.5 km in the day. This avoidance represents an effective habitat loss, but the proportion of feeding area lost due to the presence of these two wind farms, in relation to the total feeding area, is relatively small and is considered of little biological importance. Avoidance behaviour reduces the collision with turbines. The displacement of birds because of wind farm installations makes the collision risk at the two installations low. The predicted collision rates of common eiders at Nysted were 0.02 per cent, which means 45 birds over a total of 235,000 passing each autumn in the area. Monitoring has also confirmed that water-birds (mainly eider) reduce their flight altitude, below rotor height, at the Nysted wind farm (DEA, 2006).

Avoidance observed in Nysted and Horns Rev affects flying, resting and foraging between turbines. New wind farm proposals in the same area have to be carefully analysed because they may cause important habitat loss for certain species (DEA, 2006).

EIAs on marine ecosystems must take into account the cumulative effects from all the wind farms in the surrounding area, including cable connections to the network on the mainland (Exo et al, 2003).

During the last several years, a lot of methodologies on collision risk models, baseline surveys both using ship and aerial techniques and post-construction monitoring have been developed. This data is needed to properly assess and predict the future impacts of proposed wind farms (Desholm et al, 2006). Several sophisticated technologies such as radar and infra-red cameras have helped to gather a better understanding.

When there is not enough knowledge about specific species or taxonomic groups in unstudied habitats, the potential disturbance distances could be unknown. The most appropriate approach to define the disturbance distance may be to determine the bird numbers at different ranges of distances from wind farm, ensuring that all the affected area is covered in the study (Percival, 2003).

There is a common opinion on the need for more information about potential impacts of wind farms on birds (Desholm et al, 2006; Drewitt and Langston 2006; Exo et al, 2003; Fox et al, 2006; Huppop et al, 2006). Further research is required on avian responses to wind farms, models to predict the future impacts of a new single wind farm installation and groups of wind farms on an area, the collection of information on bird movements to design the marine sanctuaries of birds, and data gathering standardisation methodologies.

Mitigation measures for onshore schemes are also applicable to offshore wind farms.

>> Ship collisions, Radar and radio signals

| Acknowledgements | Sitemap | Partners | Disclaimer | Contact | ||

|

coordinated by  |

supported by  |

The sole responsibility for the content of this webpage lies with the authors. It does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the European Communities. The European Commission is not responsible for any use that maybe made of the information contained therein. |