MAIN PUBLICATION :

| Home � ECONOMICS � Wind Power at the Spot Market � Power markets |

|

Power Markets

As part of the gradual liberalisation of the EU electricity industry, power markets are increasingly organised in a similar way, where a number of closely related services are provided. This applies to a number of liberalised power markets, including those of the Nordic countries, Germany, France and the Netherlands. Common to all these markets is the existence of five types of power market:

-

Bilateral electricity trade or OTC (over the counter) Trading: Trading takes place bilaterally outside the power exchange, and prices and amounts are not made public.

Bilateral electricity trade or OTC (over the counter) Trading: Trading takes place bilaterally outside the power exchange, and prices and amounts are not made public.

The day-ahead market (spot market): A physical market where prices and amounts are based on supply and demand. Resulting prices and the overall amounts traded are made public. The spot market is a day ahead-market where bidding closes at noon for deliveries from midnight and 24 hours ahead.

The intraday market: Quite a long time period remains between close of bidding on the day-ahead market, and the regulating power market (below). The intraday market is therefore introduced as an 'in between market', where participants in the day-ahead market can trade bilaterally. Usually, the product traded is the one-hour long power contract. Prices are published and based on supply and demand.

The regulating power parket (RPM): A real-time market covering operation within the hour. The main function of the RPM is to provide power regulation to counteract imbalances related to day-ahead operation planned. Transmission System Operators (TSOs) alone make up the demand side of this market and approved participants on the supply side include both electricity producers and consumers.

-

The balancing market: This market is linked to the RPM and handles participant imbalances recorded during the previous 24-hour period of operation. The TSO alone acts on the supply side to settle imbalances. Participants with imbalances on the spot market are price takers on the RPM/balance market.

The day-ahead and regulating markets are particularly important for the development and integration of wind power in the power systems. The Nordic power exchange, NordPool, will be described in more detail in the following section as an example of these power markets.

THE NORDIC POWER MARKET - NordPool SPOT MARKET

The NordPool spot market (Elspot) is a day-ahead market, where the price of power is determined by supply and demand. Power producers and consumers submit their bids to the market 12 to 36 hours in advance of delivery, stating the quantities of electricity supplied or demanded and the corresponding price. Then, for each hour, the price that clears the market (balancing supply with demand) is determined at the NordPool power exchange.

In principle, all power producers and consumers can trade at the exchange, but in reality, only big consumers (distribution and trading companies and large industries) and generators act on the market, while the smaller companies form trading cooperatives (as is the case for wind turbines), or engage with larger traders to act on their behalf. Approximately 45 per cent of total electricity production in the Nordic countries is traded on the spot market. The remaining share is sold through long-term, bilateral contracts, but the spot price has a considerable impact on prices agreed in such contracts. In Denmark, the share sold at the spot market is as high as 80 per cent.

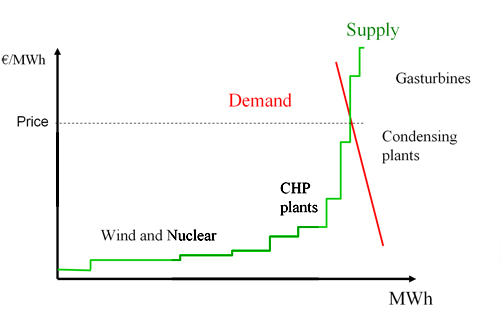

Figure 5.1: Supply and Demand Curve for the NordPool Power Exchange

Source: Risø DTU

Figure 5.1 shows a typical example of an annual supply and demand curve for the Nordic power system. As shown, the bids from nuclear and wind power enter the supply curve at the lowest level, due to their low marginal costs, followed by combined heat and power plants; while condensing plants are those with the highest marginal costs of power production. Note that hydro power is not identified on the figure, since bids from hydro tend to be strategic and depend on precipitation and the level of water in reservoirs.

In general, the demand for power is highly inelastic (meaning that demand remains almost unchanged in spite of a change in the power price), with mainly Norwegian and Swedish electro-boilers, and power intensive industry contributing to the very limited price elasticity.

If power can flow freely in the Nordic area - that is to say, transmission lines are not congested, then there will only be one market price. But if the required power trade cannot be handled physically, due to transmission constraints, the market is split into a number of sub-markets, defined by the pricing areas. For example, Denmark splits into two pricing areas (Jutland/Funen and Zealand). Thus, if more power is produced in the Jutland/Funen area than consumption and transmission capacity can cover, this area would constitute a sub-market, where supply and demand would balance out at a lower price than in the rest of the NordPool area.

THE NORDIC POWER MARKET - THE REGULATING MARKET

Imbalances in the physical trade on the spot market must be levelled out in order to maintain the balance between production and consumption, and to maintain power grid stability. Totalling the deviations from bid volumes at the spot market yields a net imbalance for that hour in the system as a whole. If the grid is congested, the market breaks up into area markets, and equilibrium must be established in each area. The main tool for correcting such imbalances, which provides the necessary physical trade and accounting in the liberalised Nordic electricity system, is the regulating market.

The regulating power market and the balancing market may be regarded as one entity, where the TSO acts as an important intermediary or facilitator between the supply and demand of regulating power. The TSO is the body responsible for securing the system functioning in a region. Within its region, the TSO controls and manages the grid, and to this end, the combined regulating power and balancing market is an important tool for managing the balance and stability of the grid. The basic principle for settling imbalances is that participants causing or contributing to the imbalance will pay their share of the costs for re-establishing the balance. Since September 2002, the settling of imbalances among Nordic countries has been done based on common rules. However, the settling of imbalances within a region differs from country to country. Work is being done in Nordel to analyse the options for harmonising these rules in the Nordic countries.

If the vendors’ offers or buyers’ bids on the spot market are not fulfilled, the regulating market comes into force. This is especially important for wind electricity producers. Producers on the regulating market have to deliver their offers 1-2 hours before the hour of delivery, and power production must be available within 15 minutes of notice being given. For these reasons, only fast-response power producers will normally be able to deliver regulating power.

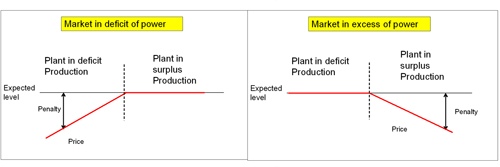

It is normally only possible to predict the supply of wind power with a certain degree of accuracy 12-36 hours in advance. Consequently, it may be necessary to pay a premium for the difference between the volume offered to the spot market and the volume delivered. Figure 5.2 shows how the regulatory market functions in two situations: a general deficit on the market (left part of the figure) and a general surplus on the market (right part of figure).

If the market tends towards a deficit of power, and if power production from wind power plants is lower than offered, other producers will have to adjust regulation (up) in order to maintain the power balance. In this case, the wind producer will be penalised and get a lower price for his electricity production than the spot market price. The further off-track the wind producer is, the higher the expected penalty. The difference between the regulatory curves and the stipulated spot market price in Figure 5.2 illustrates this. If wind power production is higher than the amount offered, wind power plants effectively help to eliminate market deficit and therefore receive the spot price for the full production without paying a penalty.

If the market tends towards an excess of power, and if power production from the wind power plant is higher than offered, other producers will have to adjust regulation (down) in order to maintain the power balance. In this case, the wind producer will be penalised and get a lower price for his electricity production than the spot market price. Again, the further off track the wind producer, the higher the expected premium. However, if wind power production is lower than the bid, then wind power plants help to eliminate surplus on the market, and therefore receive the spot price for the full production without paying a penalty.

Figure 5.2: The Functioning of the Regulatory Market

Source: Risø DTU

Until the end of 2002, each country participating in the NordPool market had its own regulatory market. In Denmark, balancing was handled by agreements with the largest power producers, supplemented by the possibility of TSOs buying balancing power from abroad if domestic producers were too expensive or unable to produce the required volumes of regulatory power. A common Nordic regulatory market was established at the beginning of 2003 and both Danish areas participate in this market.

In Norway, Sweden and Finland, all suppliers on the regulating market receive the marginal price for power regulation at the specific hour. In Denmark, market suppliers get the price of their bid to the regulation market. If there is no transmission congestion, the regulation price is the same in all areas. If bottlenecks occur in one or more areas, bids from these areas on the regulating market are not taken into account when forming the regulation price for the rest of the system, and the regulation price within the area will differ from the system regulation price.

In Norway, only one regulation price is defined and this is used both for sale and purchase at the hour when settling the imbalances of individual participants. This implies that participants helping to eliminate imbalances are rewarded even if they do not fulfil their actual bid. Thus if the market is in deficit of power and a wind turbine produces more than its bid, then the surplus production is paid a regulation premium corresponding to the penalty for those plants in deficit.

| Acknowledgements | Sitemap | Partners | Disclaimer | Contact | ||

|

coordinated by  |

supported by  |

The sole responsibility for the content of this webpage lies with the authors. It does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the European Communities. The European Commission is not responsible for any use that maybe made of the information contained therein. |