MAIN PUBLICATION :

| Home � ECONOMICS � Employment |

|

CHAPTER 7: EMPLOYMENT

Employment in the Wind Energy Sector

WIND ENERGY EMPLOYMENT IN EUROPE

Wind energy companies in the EU currently employ around 108,600 people. For more information on wind energy employment, please consult the 'Wind at Work' report published by EWEA in January 2009.

For the purposes of this report, direct jobs relate to employment in wind turbine manufacturing companies and with sub-contractors whose main activity is supplying wind turbine components. Also included are wind energy promoters, utilities selling electricity from wind energy and major R&D, engineering and specialised wind energy services. Any companies producing components, providing services or sporadically working in wind-related activities are deemed to provide indirect employment.

Table 7.1: Direct Employment from Wind Energy Companies in Selected European Countries.

Country No. of direct jobs Austria 700 Belgium 2,000 Bulgaria 100 Czech Republic 100 Denmark 23,500 Finland 800 France 7,000 Germany 38,000 Greece 1,800 Hungary 100 Ireland 1,500 Italy 2,500 The Netherlands 2,000 Poland 800 Portugal 800 Spain 20,500 Sweden 2,000 United Kingdom 4,000 Rest of EU 400 TOTAL 108,600 Source: Own estimates, based on EWEA (2008a); ADEME (2008); AEE (2007); DWIA (2008); BMU (2008).

The addition of indirect employment affects results significantly. The European Commission, in its EC Impact Assessment on the Renewable Energy Roadmap, (EC, 2006) found that 150,000 jobs were linked to wind energy. The European Renewable Energy Council (EREC, 2007) report foresees a workforce of 184,000 people in 2010, but the installed capacity for that year has probably been underestimated. Therfore, the figure for total direct and indirect jobs is estimated at approximately 154,000 jobs.

These two figures of 108,600 direct and 154,000 total jobs can be compared with the results obtained by EWEA in its previous survey for Wind Energy–The Facts (2004) of 46,000 and 72,275 workers, respectively. The growth experienced between 2003 and 2007 (236 per cent) is consistent with the evolution of the installed capacity in Europe (276 per cent - EWEA 2008) during the same period and with the fact that most of the largest wind energy companies are European.

A significant proportion of the direct wind energy employment (around 75 per cent) is in three countries, Denmark, Germany and Spain, whose combined installed capacity adds up to 70 per cent of the total in the EU. Nevertheless, the sector is less concentrated now than it was in 2003, when these three countries accounted for 89 per cent of the employment and 84 per cent of the EU installed capacity. This is due to the opening of manufacturing and operation centres in emerging markets and to the local nature of many wind-related activities, such as promotion, O&M, engineering and legal services.

Germany (BMU 2006 and 2008) is the country where most wind-related jobs have been created, with around 38,000 directly attributable to wind energy companies and a slightly higher amount from indirect effects. According to the German Federal Ministry of the Environment, in 2007 over 80 per cent of the value chain in the German wind energy sector was exported.

In Spain (AEE, 2007), direct employment is slightly over 20,781 people. When indirect jobs are taken into account, the figure goes up to 37,730. According to the AEE, 30 per cent of the jobs are in manufacturing companies; 34 per cent in installation, O&M and repair companies, 27 per cent in promotion and engineering companies and 9 per cent in other branches.

Denmark (DWIA, 2008) has around 23,500 employees in wind turbine and blade manufacturing and major sub-component corporations . When indirect jobs are taken into account, the number goes up to 23,500.

The launch of new wind energy markets has fostered the creation of employment in other EU countries. Factors such as market size, proximity to one of the three traditional leaders, national regulation and labour costs determine the industry structure, but the effect is always positive.

France (2,454 MW, 888 MW added in 2007, and an estimated figure of 7,000 wind energy jobs), for instance, shows a wealth of small developers, consultants, engineering and legal service companies. All the large wind energy manufacturers and developers and some utilities have opened up a branch in this country. France also counts on several wind turbine and component manufacturers producing in its territory.

In the UK, the importance of offshore wind energy and small-scale wind turbines is reflected by the existence of many job-creating businesses in this area. This country also has some of the most prestigious wind energy engineering and consultancy companies. The British Wind Energy Association is conducting a study of present and future wind energy employment; preliminary results point to the existence of around 4,000 to 4,500 direct jobs.

Another example is Portugal, where the growth of the market initially relied on imported wind turbines. From 2009 onwards, two new factories will be opened, adding around 2,000 new jobs to the 800 that already exist.

Some other EU Member States, such as Italy, Greece, Belgium, the Netherlands, Ireland and Sweden, are also in the 1,500 to 2,500 band. The situation in the new Member States is diverse, with Poland in a leading position. Wind energy employment will probably rise significantly in the next three to five years, boosted by a combination of market attractiveness, a highly skilled labour force and lower production costs.

In terms of gender, the survey conducted by EWEA shows that males make up 78 per cent of the workforce. In the EU labour market as a whole, the figure is is 55.7 per cent. Such a bias reflects the traditional predominance of men in production chains, construction work and engineering.

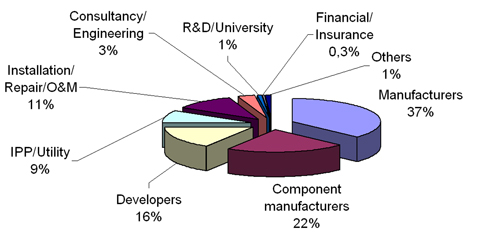

By type of company, wind turbine and component manufacturers account for most of the jobs (59 per cent). Within these categories, companies tend to be bigger and thus employ more people.

Figure 7.1: Direct Employment by Type of Company, According to EWEA Survey

Source: EWEA (2008a)

Wind energy figures can be measured against the statistics provided by Eurostat. The energy sector employs 2.69 million people, accounting for 1.4 per cent of total EU employment. Approximately half this amount is active in the production of electricity, gas, steam and hot water. Employment from the wind energy sector would then make up around 7.3 per cent of that amount; and it should be noted wind energy currently meets 3.7 per cent of EU electricity demand. Although the lack of specific data for electricity production prevents us from making more accurate comparisons, this shows that wind energy is more labour intensive than the other electricity generating technologies. This conclusion is consistent with earlier research.

Finally, there is a well documented trend of energy employment decline in Europe, particularly marked in the coal sector. For instance, British coal production and employment have dropped significantly, from 229,000 workers in 1981 to 5,500 in 2006. In Germany, it is estimated that jobs in the sector will drop from 265,000 in 1991 to less than 80,000 in 2020. In EU countries, more than 150,000 utility and gas industry jobs disappeared in the second half of the 1990s and it is estimated that another 200,000 jobs wll be lost during the first half of the 21st century (UNEP, ILO, ITUC, 2007). The outcomes set out in the previous paragraphs demonstrate that job losses in the European energy sector are independent of renewable energy deployment and that the renewable energy sector is, in fact, helping to mitigate these negative effects in the power sector.

JOB PROFILES OF THE WIND ENERGY INDUSTRY

The lack of any official classification of wind energy companies makes it difficult to categorise wind energy jobs. Table 7.2 summarises the main profiles required by wind energy industries, according to the nature of their core business.

Table 7.2: Typical Wind Energy Job Profiles Demanded by Different Types of Industry

Company type Field of activity Main job profiles Wind energy manufacturers Wind turbine producers, including manufacturers of major sub-components and assembly factories.

- Highly qualified chemical, electrical, mechanical & materials engineers dealing with R&D issues, product design, management and quality control of production process.

- Semi-skilled and non-skilled workers for the production chains.

- Health and safety experts.

- Technical staff for the O&M and repair of the wind turbines.

- Other supporting staff (including administrative, sales managers, marketing and accounting).

Developers Manage all the tasks related to the development of wind farms (planning, permits, construction etc).

- Project managers (engineers, economists) to coordinate the process.

- Environmental engineers and other specialists to analyse the environmental impacts of wind farms.

- Programmers and meteorologists for wind energy forecasts and prediction models.

- Lawyers and economists to deal with the legal and financial aspects of project development.

- Other supporting staff (including administrative, sales managers, marketing and accounting).

Construction, repair and O&M Construction of the wind farm, regular inspection and repair activities.

- Technical staff for the O&M and repair of wind turbines.

- Electrical and civil engineers for the coordination of construction works.

- Health and safety experts.

- Specialists in the transport of heavy goods.

- Electricians.

- Technical staff specialised in wind turbine installation, including activities in cranes, fitters and nacelles.

- Semi-skilled and non-skilled workers for the construction process.

- Other supporting staff (including administrative, sales managers and accounting).

Independent power producers, utilities Operation of the wind farm and sale of the electricity produced.

- Electrical, environmental and civil engineers for the management of plants.

- Technical staff for the O&M of plants, if this task is not sub-contracted.

- Health and safety experts.

- Financiers, sales and marketing staff to deal with the sale of electricity.

- Other supporting staff (including administrative and accounting)..

Consultancies, legal entities, engineering, financial institutions, insurers, R&D centres, others. Diverse specialised activities linked to the wind energy business.

- Programmers and meteorologists for the analysis of wind regimes and output forecasts.

- Engineers specialised in aerodynamics, computational fluid dynamics and other R&D areas.

- Environmental engineers.

- Energy policy experts.

- Experts in social surveys, training and communication.

- Financiers and economists.

- Lawyers specialised in energy and environmental matters.

- Marketing personnel, event organisers.

THE SHORTAGE OF WORKERS

In the last two to three years, wind energy companies have repeatedly reported a serious shortage of workers, especially within certain fields. This scarcity coincides with a general expansion of the European economy, where growth rates have been among the fastest since the end of the Second World War. An analysis of Eurostat (2008b) statistics proves that job vacancies have been difficult to cover in all sectors. The rotation of workers is high, both for skilled and non-skilled workers.

In the case of wind energy, the general pressure provoked by strong economic growth is complemented by the extraordinary performance of the sector since the end of the 1990s. In the 2000-2007 period, wind energy installations in the EU increased by 339 per cent (EWEA, 2008b). This has prompted an increase in job offers in all the sub-sectors, especially in manufacturing, maintenance and development activities.

Generally speaking, the shortage is more acute for positions that require a high degree of experience and responsibility:

- From a manufacturer’s point of view, two major bottlenecks arise: one relates to engineers dealing with R&D, product design and the manufacturing processes; the other to O&M and site management activities (technical staff).

- In turn, wind energy promoters lack project managers; the professionals responsible for getting the permits in the country where a wind farm is going to be installed. These positions require a combination of specific knowledge of the country and wind energy expertise, which is difficult to gain in a short period of time.

- Other profiles, such as financiers or sales managers can sometimes be hard to find, but generally this is less of a problem for wind energy companies, possibly because the necessary qualifications are more general.

- The picture for the R&D institutes is not clear: of the two consulted one reported no problems, while the other complained that it was impossible to hire experienced researchers. It is worth noting that the remuneration offered by R&D centres, especially if they are governmental or university-related, is below the levels offered by private companies.

The quality of the university system does not seem to be at the root of the problem, although recently graduated students often need an additional specialisation that is given by the wind company itself. The general view is that the number of engineers graduating from European universities on an annual basis does not meet the needs of modern economies, which rely heavily on manufacturing and technological sectors.

In contrast, there seems to be a gap in the secondary level of education, where the range and quality of courses dealing with wind-related activities (mainly O&M, health and safety, logistics and site management) are inadequate. Policies aimed at improving the educational programmes at pre-university level - dissemination campaigns, measures to encourage worker mobility and vocational training for the unemployed - can help overcome the bottleneck, and at the same time ease the transition of staff moving from declining sectors.

| Acknowledgements | Sitemap | Partners | Disclaimer | Contact | ||

|

coordinated by  |

supported by  |

The sole responsibility for the content of this webpage lies with the authors. It does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the European Communities. The European Commission is not responsible for any use that maybe made of the information contained therein. |